Annual Water Quality Monitoring

On April 11 and May 15, 2024, FODM volunteers collected sediment samples from the bed of the unnamed stream that flows through Mount Vernon Park, Westgrove Dog Park, River Towers Condominium properties and into Dyke Marsh. FODM started monitoring this stream in 2016 in partnership with the Northern Virginia Soil and Water Conservation District (NVSWCD).

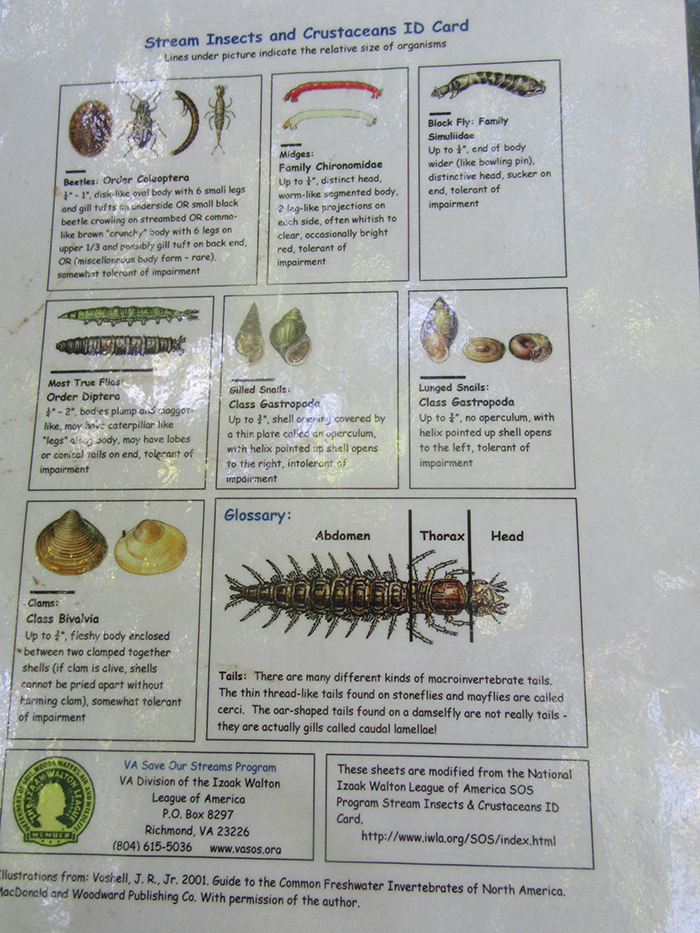

The protocols require taking 20 samples within a 300-foot span, with the goal of identifying 100 living invertebrates. The invertebrate types in a stream is one indicator of stream quality. Some species are tolerant of pollution and degraded environments and others are very sensitive to pollution.

The water quality scoring scale is 0 to 24, meaning 24 is a healthy stream. A stream scoring less than eight is considered to be in ecologically unacceptable condition; a score of 8 to14, partially acceptable; and a score greater than 14, acceptable.

On April 11, the stream scored 18, tied for the highest ever recorded at the site. On May 16 the stream scored nine, a score which NVSWCD leader Ashley Palmer described as an “indeterminate ecological stream score.” On April 11, the group collected 146 organisms; on May 16, 84.

This stream is both intermittent and ephemeral, fed by stormwater overflow from upstream development and from underground springs. The group collects samples from the streambanks, woody debris, riffles and submerged aquatic vegetation.

In 2023, Palmer summarized the then seven years of monitoring: “Overall, low unofficial stream scores and a low number of total organisms collected at each sampling likely indicate that [the creek] is in poor ecological health. A healthy stream is abundant in both quantity and biodiversity of macroinvertebrates, which serve many important functions in aquatic food webs. . .”

She recommends continued monitoring “because it is a tributary to Dyke Marsh and one of the ways to check in on the health of Dyke Marsh is to monitor the small streams that feed into it. This creek has experienced erosion in the past and it’s important to keep an eye out for indicators for this problem arising in the future.”

This NVSWCD table shows results since 2016:

For more information, visit Virginia Save Our Streams, at www.vasos.org.

|

| The group scooped up sediments from the stream bed. All photos by Glenda Booth. |

|

| They searched through the sediments for invertebrates. (1 of 2) |

|

| They searched through the sediments for invertebrates. (2 of 2) |

|

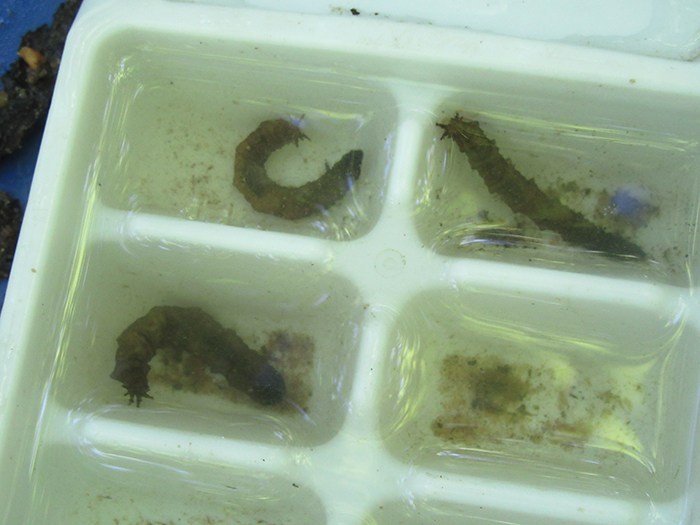

| They put the “critters,” like these wiggly craneflies, in water in an ice tray. |

|

| These cards help volunteers identify the invertebrates they find. |

|

| Skunk cabbage plants (Symplocarpus foetidus) were thriving along the stream bank. |

|

| Deer tongue (Dichanthelium clandestinum) were also thriving along the stream bank. |

|

| Ashley Palmer supervises water quality monitoring for the Northern Virginia Soil and Water Conservation District. |

Friends of Dyke Marsh, Inc. is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization.

Friends of Dyke Marsh, Inc. is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization.