The Results of the 2020 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey

By Larry Cartwright, Breeding Bird Survey Coordinator

Volunteers conducted the 2020 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey from May 23 to July 4, 2020. Any data collected outside of this period that confirmed breeding activity was entered into the database. This permitted us to filter out most migrants that do not breed in Dyke Marsh. I also included information provided from reliable individuals to supplement data reported by the survey teams. The FODM Sunday morning bird walks provided no additional data since FODM had to cancel them in early 2020 because of the COVID-19 virus.

The survey tract encompassed the Belle Haven picnic area, the Belle Haven marina, the open marsh, that portion of the Big Gut known as west Dyke Marsh that extends under the George Washington Memorial Parkway west to behind the River Towers Condominiums, the Potomac River from the shoreline extending to the channel of the river and the adjacent woodland and open area south of Hunting Creek to south of Morningside Lane.

Methodology

The survey methodology uses behavioral criteria to determine the breeding status of all species found in the survey tract. Species are placed into one of four categories:

- confirmed breeder,

- probable breeder,

- possible breeder and

- present

Despite the difficulties in conducting the survey under restrictive COVID-19 pandemic protocols, our teams did quite well. We found 75 species at Dyke Marsh during 2020. We confirmed 46 species as breeders, seven as probable breeders, and 13 as possible breeders. We listed an additional nine species as present. They were a combination of colonial breeding waterbird species not using a rookery inside the survey tract, species in unsuitable breeding habitat and migrants still headed north.

Prothonotary Warblers, a Highlight

|

|

| Adult prothonotary warbler (Protonotaria citrea) shown feeding fledged youngster. Photo by Ed Ed |

The prothonotary warblers’ (Protonotaria citrea) impressive breeding success was a highlight of the 2020 survey. When I became compiler of the breeding bird survey in 1994, volunteers usually found prothonotary warblers from the Big Gut bridge across from Tulane Drive south to below Morningside Lane. The birds sometimes used nest cavities in short snags right along the shoreline of the Big Gut or Potomac River, making confirmation of breeding rather easy. Finding other nests away from the immediate shoreline was impossible, but eventually a lucky volunteer would spot an adult carrying food or feeding fledged young.

Over a decade ago, perhaps one or two prothonotary warblers began occupying territory along the Haul Road trail and on Coconut Island, probably because the presence of standing water and the availability of snags made the habitat increasingly appealing to the birds. In 2020, surveyors reported prothonotary warblers at the Belle Haven marina, the Haul Road trail entrance, near the Haul Road trail overlook that we unofficially call Dead Beaver Beach and beyond the dogleg turn in the Haul Road trail, perhaps representing four or more territorial males.

Prothonotary warblers established as many as 10 additional territories in the south marsh. The first confirmation of breeding came from north of Morningside Lane on June 5 where a male was transporting a mouthful of food to nestlings. On July 11, a prothonotary warbler was feeding two fledged young at the Big Gut bridge, followed by an adult feeding two young north of the Haul Road trail dogleg on July 26 and a fledged youngster with a parent at the Haul Road trail entrance on August 10. Quite impressive.

Mourning Doves

|

|

| Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) sits on nest with nestling visible quite early in the breeding season. Photo by Laura Sebastianelli |

|

|

|

| A blue-gray gnatcatcher (Polioptila crinitus) sits on lichen-adorned nest on the Haul Road. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

The mourning doves’ (Zenaida macroura) breeding season was equally impressive, even for this prolific species. These birds start the breeding season early in the spring and continue into late summer. 2020 was no different. However, we found a mourning dove breeding pair that may hold a Dyke Marsh record for producing the earliest fledged youngsters. On March 27, a mourning dove was sitting on a nest with two young. On April 3, the two now well-developed young were still in the nest but fledged by the following morning. If you consider a short egg-laying period followed by a 14-day incubation and a 15-day nestling period, nest construction would have had to have commenced in late February. Now that is typical in the southern U.S., but not in northern Virginia as far as I know. Will wonders never cease?

Most of the expected songbird species that occupy the wooded areas near marsh habitat during the breeding season were present in 2020. Among them were yellow warblers (Setophaga petechia) and song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), both of which were absent in 2019 but occupied territory in 2020 and were confirmed as breeders. Baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula) were present in 2019, but survey teams were unable to find evidence of breeding. In 2020, we discovered a Baltimore oriole nest at the Haul Road trail dogleg.

Some of the other more notable confirmed breeders documented during the 2020 survey include great crested flycatchers (Myiarchus crinitus), eastern kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus), warbling (Vireo gilvus) and red-eyed vireos (Vireo olivaceus), the extremely prolific blue-gray gnatcatchers (Polioptila caerulea), orchard orioles (Icterus spurius) and common yellowthroats (Geothlypis trichas). Remaining conspicuously missing in 2020 was the northern parula (Setophaga americana), which has not been recorded as a breeder or even occupying territory since 2017.

Marsh Wrens, Least Bitterns

We conducted fewer canoe surveys in 2020 than in normal years because of COVID-19 concerns, but we were able to gather some data on the status of marsh wrens (Cistothorus palustris) and least bitterns (Ixobrychus exilis) from several of our outings. A June 19 survey revealed the presence of at least two probable territorial marsh wrens in the northeast passage in what we have termed the “northeast passage” as an unofficial location reference, a tributary of the upper Big Gut. By August 5, one of the birds had constructed three nests, but there was no evidence that any had been accepted and occupied by a female. Only one female-occupied nest has been reported since 2014, and the prospects for the marsh wrens’ recovery at Dyke Marsh currently seems bleak.

|

|

| A least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) peers out though the marsh vegetation. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

Surveys of the Big Gut found most least bitterns occupying the northeast passage, with a high count of four recorded on June 12. The presence of a female on July 14 raised some hopes for breeding confirmation, but we were to be disappointed. In the north marsh, a few least bitterns occupied the tributaries of the Little Gut, but we found no evidence of breeding at that location either. Indeed, least bitterns have not been confirmed as breeders for five years, which only adds to the concern for the future of this species at Dyke Marsh.

Raptors

|

|

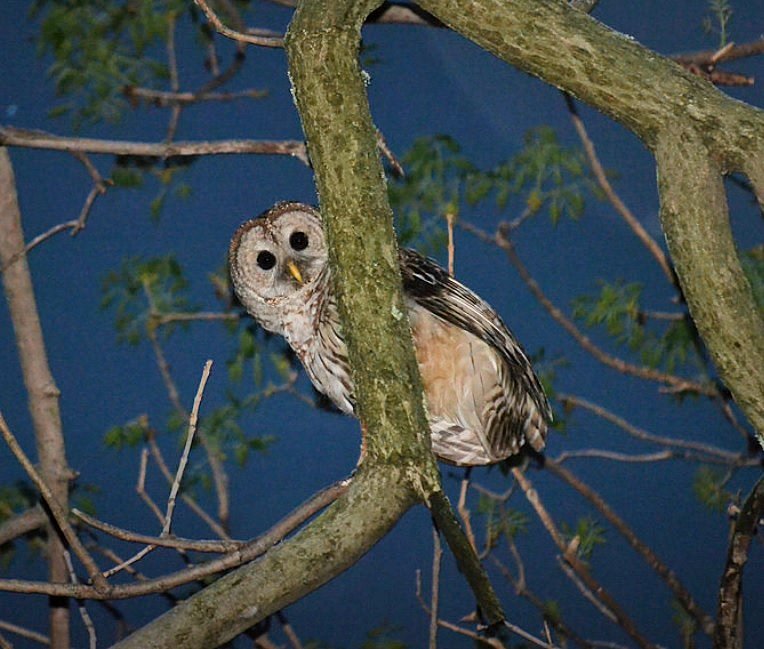

| A recently fledged barred owl (Strix varia) on the right perched near one of its parents. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

A highlight of raptors’ breeding was early April reports of a barred owl (Strixvaria) family group consisting of a breeding pair and two recently fledged young near the Haul Road trail entrance. We were aware of an adult presence through several sightings beginning in early March, but the debut of the youngsters on April 3 thrilled the birders and nature lovers who happened to be there to see them. The birds were celebrities for a few days before they began to recede into the thicker vegetation and became harder to spot. The youngsters reportedly were active and healthy as of June 22, the last day they were reported.

A red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) pair made a nesting attempt near the River Towers condominiums in 2020. We identified a fledged youngster in the same area the previous year, but this was the first time that the survey ever recorded a red-shouldered hawk nest. Nest construction occurred in March. An April 27 outing documented the presence of a fluffy white young. Our delight was short-lived as the youngster perished soon after May 5, the last day the nest was observed to be occupied.

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) nest along the Haul Road trail, in its third active season, was popular among nature photographers and others despite the pandemic. The breeding pair did not disappoint. Observers documented two young by mid-March and for the next two and a half months, the developing nestlings provided entertainment for many visitors. The birds fledged on June 3. The Tulane Drive nest produced at least two young based upon an observation of a family group near the nest site in July, but the Morningside Lane nest apparently failed as volunteers never saw young and were unable to find adults at the nest site after May 11.

Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) did not have a banner year at Dyke Marsh. The birds constructed 10 nests, all of which could be monitored easily from land with a scope. One nest built on a crane on a barge in the channel was abandoned, or perhaps removed, by June 1. Of the remining nine nests, only three produced young. The nest residing on the platform beside the marina boat ramp fledged a single young osprey in early August, a month later than the normal fledging date around Independence Day. This may be attributed to the fact that the birds delayed construction for more than a week after they were first spotted at Dyke Marsh on March 10. The other two successful nests, each producing multiple nestlings, were at Porto Vecchio condominiums just north of Dyke Marsh and they also seemed to have started nesting later than normal. The fledging date for the young occupying the two Porto Vecchio nests was on or around July 21.

I have been compiler of the Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey since 1994 and have witnessed many changes in the breeding status and density of several avian species at Dyke Marsh since then. The decline of the marsh wren and least bittern, the return of the bald eagle and the ups and downs of several songbirds like prothonotary and yellow warblers are a few examples. These events have all been recorded by volunteers of the Friends of Dyke Marsh.

Volunteers are valuable to continuing this survey and I would like to acknowledge those who participated in 2020. In alphabetical order, they are as follows: Dave Arnold, Eldon Boes, Glenda Booth, Jessica Bowser, John Cushing, Ed Eder, Deborah Hammer, Nathan Harms, Todd Kiraly, Joan Mashburn, Nick Nichols, Roger Miller, Mary Parrish, Rich Rieger,Laura Sebastianelli, Robert Smith, Dixie Sommers and Sherman Suter.

The 2020 Breeding Bird Survey Results:

Confirmed - 46 Species: Canada Goose, Wood Duck, Mallard, Mourning Dove, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Red-shouldered Hawk, Barred Owl, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Northern Flicker, Pileated Woodpecker, Great Crested Flycatcher, Eastern Kingbird, Warbling Vireo, Red-eyed Vireo, Blue Jay, Fish Crow, Tree Swallow, N. Rough-winged Swallow, Barn Swallow, Carolina Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, White-breasted Nuthatch, House Wren, Carolina Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, American Robin, Gray Catbird, Northern Mockingbird, European Starling, Cedar Waxwing, House Sparrow, House Finch, American Goldfinch, Song Sparrow, Orchard Oriole, Baltimore Oriole, Red-winged Blackbird, Brown-headed Cowbird, Common Grackle, Prothontary Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, Northern Cardinal.

Probable - 7 Species: Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Willow Flycatcher, Purple Martin, Marsh Wren, American Redstart, Indigo Bunting.

Possible - 13 Species: Hooded Merganser, Wild Turkey, Chimney Swift, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Least Bittern, Green Heron, Belted Kingfisher, Acadian Flycatcher, Eastern Phoebe, American Crow, Brown Thrasher, Northern Parula, Scarlet Tanager.

Present - 9 Species: Rock Pigeon, Whimbrel, Ringbilled Gull, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Black Vulture, Alder Flycatcher, Bobolink, Blackpoll Warbler.

Definition of Categories:

Confirmed Breeder: Any species for which there is at minimum evidence of a nest. A species need not successfully fledge young to be placed in the confirmed category.

Probable Breeder: Any species engaged in pre-nesting activity, such as a male on territory, courtship behavior, or even the presence of a pair, but for which there is no evidence of a nest. Since birds can and do sing and display to females during migration, this category cannot be used until the safe dates are reached.

Possible Breeder: Any species, male or female, observed in suitable habitat, but giving no hard evidence of breeding. Unless actively breeding, all birds in suitable habitat before the start of the safe date are placed in this category.

Present: Any species observed that is not in suitable habitat or out of its breeding range. It also applies to colonial water birds in the survey tract not associated with a rookery in the tract.

Definition of Safe Dates

We use safe dates as a means of deciding if a bird can be considered a breeder or a migrant. Safe dates are simply defined as a period beginning when all members of a given species have ceased to migrate in the spring and ending when they begin to migrate in the fall. Unless a bird is engaged in behavior that confirms breeding, it will be placed no higher than in the possible breeder category if it is observed outside the safe dates assigned to that species.

The Results of the 2019 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey

By Larry Cartwright, Breeding Bird Survey Coordinator

| Larry Cartwright Marks 20 Years at Breeding Bird Survey | |

| The Friends of Dyke Marsh honored Larry Cartwright at the quarterly meeting on May 16, 2012, with a certificate of appreciation for organizing and leading the survey for 20 years. This activity, a continuing biological inventory of the birds of the Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve, has provided trend information since the 1960s. The Friends also gave Larry a portrait a prothonotary warbler, Larry's favorite bird. FODM President Glenda Booth presided. |  |

Volunteers conducted the 2019 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey between May 25 and July 4, but any data collected outside of this period that confirmed a breeding species was entered into the database. This permitted us to filter out most migrants that do not use the marsh or surrounding habitat to breed. I also included information provided from the Sunday morning walks and reliable individuals to supplement data reported by the survey teams. The survey tract encompasses the Belle Haven picnic area, the marina, the open marsh, that portion of the Big Gut known as West Dyke Marsh that extends from the George Washington Memorial Parkway west to River Towers, the Potomac River from the shoreline to the channel, and the surrounding woodland from the mouth of Hunting Creek to south of Morningside Lane.

The breeding bird survey methodology uses behavioral criteria to determine the breeding status of each species found in the survey tract. Species are placed into one of four categories: confirmed breeder, probable breeder, possible breeder, and present. We identified 71 species at Dyke Marsh during 2019. There were 40 confirmed breeding species, 10 probable breeders, and 13 possible breeders. An additional 8 species were listed as present, but either were colonial breeding waterbird species not using a rookery inside the survey tract, species in unsuitable habitat for breeding, or migrants still transiting northern Virginia to breeding areas further north.

Adult pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) feeding fledged young. Photo by Ed EderThe 2019 survey revealed some noticeable changes in songbird presence and distribution. Some species like great crested flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus), eastern kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus), and orchard oriole (Icterus spurius) were found in their usual abundance and all bred at Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve. However, for the first time since I became compiler in 1994, yellow warblers (Setophaga petechia) and Baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula) were not confirmed as breeders. Although volunteers discovered four or five territorial Baltimore oriole males and even a male-female pair, we found no evidence of breeding. Yellow warbler males did not even attempt to establish territory. Song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), often confirmed as breeders in past years, were also absent.

Adult pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) feeding fledged young. Photo by Ed EderThe 2019 survey revealed some noticeable changes in songbird presence and distribution. Some species like great crested flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus), eastern kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus), and orchard oriole (Icterus spurius) were found in their usual abundance and all bred at Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve. However, for the first time since I became compiler in 1994, yellow warblers (Setophaga petechia) and Baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula) were not confirmed as breeders. Although volunteers discovered four or five territorial Baltimore oriole males and even a male-female pair, we found no evidence of breeding. Yellow warbler males did not even attempt to establish territory. Song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), often confirmed as breeders in past years, were also absent.

Warbling vireos (Vireo gilvus) were confirmed as breeders in 2019 and although numbers were robust around Haul Road and the Belle Haven picnic area, the density in the south marsh was dramatically diminished. Although we could easily find up to nine warbling vireos in the picnic area and Haul Road during a morning outing, it was extremely difficult to document more than two singing males while conducting a survey from the Big Gut Bridge and Tulane Drive south to Morningside Lane.

The results of the 2019 survey also indicated a drop in the number of songbird young that fledged, including the more common species like eastern kingbird and orchard oriole, where we found numerous nests of both species, but fewer than expected family groups. We found no warbling vireo nests or fledged young in 2019. Our confirmation of this species consisted of an adult carrying food to an unlocated nest.

Northern flickers (Colaptes auratus) copulating. Photo by Ed EderThere are several possibilities as to what happened during the 2019 breeding season. We have discussed the possible effect of unsettled weather and a warming climate, a reported drop in the insect and other arthropod prey base, the death of numerous pumpkin ash trees and the likelihood that 2019 was just an off year. It may be a combination of events occurring simultaneously. The death of pumpkin ash trees has opened many areas that used to produce canopy cover that may have concealed many songbird nests from predators. I received one report in 2019 of fish crows attacking and consuming eastern kingbird nestlings along the boardwalk at the end of Haul Road. Perhaps predation is becoming a more frequent event.

Northern flickers (Colaptes auratus) copulating. Photo by Ed EderThere are several possibilities as to what happened during the 2019 breeding season. We have discussed the possible effect of unsettled weather and a warming climate, a reported drop in the insect and other arthropod prey base, the death of numerous pumpkin ash trees and the likelihood that 2019 was just an off year. It may be a combination of events occurring simultaneously. The death of pumpkin ash trees has opened many areas that used to produce canopy cover that may have concealed many songbird nests from predators. I received one report in 2019 of fish crows attacking and consuming eastern kingbird nestlings along the boardwalk at the end of Haul Road. Perhaps predation is becoming a more frequent event.

Volunteer surveyors always play close attention to two prominent birds that occupy the open marsh, the marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris) and the least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis). We have found only one active marsh wren nest since 2014. Despite the lack of breeding attempts, at least a few marsh wren males occupied the marsh, even if only briefly, since 2015. The 2019 survey recorded no marsh wrens at Dyke Marsh, the first time this has happened in my tenure as compiler.

The status of the least bittern seems more precarious than ever. One caveat is that we conducted only two canoe routes in the south marsh in 2019, but canoe teams covered the marsh around the Haul Road, Little Gut, and the western edge of the marsh south of the Little Gut to Bird Island almost weekly. These canoe teams plus a land-based team yielded only two reports in early June of a least bittern in one of the tributaries of the Little Gut. The two southern canoe teams conducted their surveys in late June. Each of these teams reported one bird, both in the upper portion of the Big Gut, but at separate locations. That is the total sum of least bittern reports for 2019.

Bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) nest on Haul Road with one adult and one of two nestlings. Photo by Ed EderThe Haul Road nesting bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) were successful in the second season of this nest's existence. The novice breeding pair fledged one young bird in 2018; this year they doubled that effort with two youngsters fledging by early June. The Morningside Lane breeding pair produced at least one fledged young, but we found no fledged birds that could be associated with the Tulane Drive nest.

Bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) nest on Haul Road with one adult and one of two nestlings. Photo by Ed EderThe Haul Road nesting bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) were successful in the second season of this nest's existence. The novice breeding pair fledged one young bird in 2018; this year they doubled that effort with two youngsters fledging by early June. The Morningside Lane breeding pair produced at least one fledged young, but we found no fledged birds that could be associated with the Tulane Drive nest.

Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) built eleven nests in 2019. A nest on Bird Island was destroyed by Memorial Day weekend apparently when part of the tree supporting it broke off and a second nest built on a huge stump in the Potomac River near Porto Vecchio met a similar fate when it was washed away. Of the remaining nine nests, only half produced nestlings and fledged young. Successful nests tended to be closer to or along the shoreline while unsuccessful nests were further out in the river on pilings or other artificial structures. I have no ready explanation or theory as to why this would be the case. I initially toyed with the idea that something may have impacted the fish prey base in the open river, but there is no tangible evidence to prove that.

Finally, and much to my surprise, we added four first-time confirmed breeders to the Dyke Marsh list, consisting of one waterfowl species, two hawks, and a songbird. In April, one of our volunteers who resides at River Towers, spotted a hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus) hen with eight recently hatched young in West Dyke Marsh. The actions of a red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) pair courting and copulating in West Dyke Marsh throughout March culminated in the fledging of at least one youngster in July. Eastern bluebirds (Sialia sialus) bred in a cavity in an open park-like wooded area adjacent to the marsh in West Dyke Marsh. We observed a fledged youngster by late June. Finally, although the effort was abandoned, a nest building Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) was documented along Haul Road in mid-April.

The Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve Breeding Bird Survey would not be possible without the dedication of those citizen-scientists who collected valuable data. The Friends of Dyke Marsh and I as the compiler are pleased to acknowledge all the people who contributed time and expertise to the survey in 2019. In alphabetical order, they are: Eldon Boes, Ed Eder, Sandy Farkas, Gerry Hawkins, Clark Herbert, Ellen Kabat, Elizabeth Ketz-Robinson, Dorothy McManus, Ginny McNair, Larry Meade, Roger Miller, Nick Nichols, Rich Rieger, Don Robinson, Laura Sebastianelli, Phil Silas, Robert Smith, Dixie Sommers, Sherman Suter, Margaret Wohler, Katherine Wychulis.

The 2019 Breeding Bird Survey Results:

Confirmed - 40 Species: Canada Goose, Wood Duck, Mallard, Hooded Merganser, Mourning Dove, Osprey, Cooper's Hawk, Bald Eagle, Re-shouldered Hawk, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Northern Flicker, Pileated Woodpecker, Eastern Phoebe, Great Crested Flycatcher, Eastern Kingbird, Warbling Vireo, Blue Jay, Fish Crow, Tree Swallow, Northern Rough-winged Swallow, Barn Swallow, Carolina Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, House Wren, Carolina Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Eastern Bluebird, American Robin, Gray Catbird, Brown Thrasher, Northern Mockingbird, European Starling, Cedar Waxwing, House Sparrow, House Finch, Orchard Oriole, Red-winged Blackbird, Common Grackle, Northern Cardinal.

Probable - 10 Species: Green Heron, Barred Owl, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Acadian Flycatcher, Red-eyed Vireo, American Goldfinch, Baltimore Oriole, Prothonotary Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Indigo Bunting.

Possible - 13 Species: Chimney Swift, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Spotted Sandpiper, Least Bittern, Belted Kingfisher, Hairy Woodpecker, American Crow, White-breasted Nuthatch, Song Sparrow, Brown-headed Cowbird, American Redstart, Northern Parula, Yellow Warbler.

Present - 8 Species: Rock Pigeon, Ring-billed Gull, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, Black Vulture, Turkey Vulture, Blackpoll Warbler.

Definition of Categories:

Confirmed Breeder: Any species for which there is at minimum evidence of a nest. A species need not successfully fledge young to be placed in the confirmed category.

Probable Breeder: Any species engaged in pre-nesting activity, such as a male on territory, courtship behavior, or even the presence of a pair, but for which there is no evidence of a nest. Since birds can and do sing and display to females during migration, this category cannot be used until the safe dates are reached.

Possible Breeder: Any species, male or female, observed in suitable habitat, but giving no hard evidence of breeding. Unless actively breeding, all birds in suitable habitat before the start of the safe date are placed in this category.

Present: Any species observed that is not in suitable habitat or out of its breeding range. It also applies to colonial water birds in the survey tract not associated with a rookery in the tract.

Definition of Safe Dates: We use safe dates as a means of deciding if a bird can be considered a breeder or a migrant. Safe dates are simply defined as a period of time beginning when all members of a given species have ceased to migrate in the spring and ending when they begin to migrate in the fall. Unless a bird is engaged in behavior that confirms breeding, it will be placed no higher than in the possible breeder category if it is observed outside the safe dates assigned to that species.

The Results of the 2018 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey

By Larry Cartwright, Breeding Bird Survey Coordinator

The 2018 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey was conducted between Saturday, May 26,and Wednesday, July 4, but any data collected outside of this period that confirmed a breeding species was entered into the database. This permitted us to filter out most migrants that do not use the marsh or surrounding habitat to breed. I also included information provided from the Sunday morning walks and reliable individuals to supplement data reported by the survey teams. The survey tract encompasses the Belle Haven picnic area, the marina, the open marsh, that portion of the Big Gut known as West Dyke Marsh that extends from the George Washington Memorial Parkway west to River Towers, the Potomac River from the shoreline to the channel and the surrounding woodland from the mouth of Hunting Creek to south of Morningside Lane.

The breeding bird survey methodology uses behavioral criteria to determine the breeding status of each species that is recorded in the survey tract. Species are placed into one of four categories: confirmed breeder, probable breeder, possible breeder and present. We identified 65 species at Dyke Marsh during 2018. There were 38 confirmed breeding species, six probable breeders and 16 possible breeders. An additional five species were listed as present, but either were colonial breeding waterbird species not using a rookery inside the survey tract or migrants still moving through northern Virginia to breeding areas further north.

|

|

|

Only one male marsh wren (Cistothorus |

|

Those who have visited Dyke Marsh during the summer or have read these yearly breeding bird survey reports are aware of the plight of the marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris). Marsh wren numbers declined over 15 years and the species ceased to be a breeder after 2014. The breeding season of 2014 was the last time that volunteers documented multiple active nests. In 2015 and 2016, a handful of marsh wrens appeared in the north marsh, with perhaps two or three males briefly establishing territory, but we could not confirm breeding. During 2017, a canoe team on June 25 spotted a marsh wren carrying nesting material. A later survey team found three nests, one of which contained interior lining normally placed in an active nest by a female. A male was observed close to the nest, and I determined that this situation was enough to confirm breeding.

Unfortunately, our 2018 survey teams found no marsh wren nests, either active ones with attending females or dummy nests built by males to attract females. All we located was a solitary male that briefly set up a territory north of the Haul Road peninsula for approximately two weeks in May and another lone male singing from the marsh vegetation in the Big Gut in the south marsh on July 1. Volunteers neither saw nor heard additional marsh wrens in 2018, and with no evidence of breeding, the species once again lost its confirmed breeding status.

|

|

| Least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) numbers were down and were difficult to spot this year. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

Least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) numbers appeared down in 2018 compared to the previous year and it was difficult even to find them by canoe. Four birds were seen on one trip in the Big Gut on July 4, but none appeared to be paired. During the 2018 survey, we found only one likely breeding pair located in the narrowleaf cattails near the boardwalk at the end of the Haul Road peninsula. Subsequent searches yielded no fledged young and for the second straight year volunteers were unable to confirm least bittern as a breeder.

I stated in last year’s report that least bitterns seemed to have withdrawn from the southern half of the Big Gut, primarily because of erosion and were concentrating their activities north of that point. In 2017, an impressive nine birds were collectively recorded during one June day by three survey teams. Five of these birds, consisting of two pairs and a solitary individual, were in the north marsh and the remaining four were in the upper portion of the Big Gut. Volunteers found no birds in the lower Big Gut during the entire 2017 survey. The same distribution of least bitterns repeated itself in 2018, but there were fewer birds.

|

|

| Blue-gray gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) on nest. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

The 2018 survey also shows that while some songbird species are successfully maintaining their populations in the wooded area adjacent to the marsh, others are possibly starting to decline. Great crested flycatchers (Myiarchus crinitus), Eastern kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus), warbling vireos (Vireo gilvus), blue-gray gnatcatchers (Polioptila caerulea) and orchard orioles (Icterus spurius) continue to do well as we easily found high individual numbers, nests and fledged young for these species. For example, a high count for warbling vireos was eleven during a June 18 survey. Prothonotary warblers (Protonotaria citrea) also seem stable for now, primarily in the south marsh where there are enough cavities which they use for nesting.

Yellow warblers (Setophaga petechia) and Baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula) may present a different story. Yellow warbler nests usually can be found between the dogleg and the boardwalk at the end of the Haul Road peninsula. Although one volunteer observed a female carrying nesting material in early May, we uncovered no yellow warbler nests or saw any fledged young throughout the rest of the survey, a truly odd occurrence. As for Baltimore orioles, volunteers in 2018 tallied only one or two Baltimore orioles per survey compared to up to six individual orchard orioles. In previous years, numbers for the two oriole species have been roughly equal. Nonetheless, we documented two Baltimore oriole nests and in mid-July, saw an adult feeding a fledged youngster, so despite lower individual numbers, the species remains a confirmed breeder.

The truly puzzling species are the eastern wood-pewee (Contopus virens), Acadian flycatcher (Empidonax virescens), red-eyed vireo (Vireo olivaceus) and northern parula (Setophaga Americana), all common species in the mid-Atlantic states. Eastern wood-pewees, Acadian flycatchers, and red-eyed vireos showed up at Dyke Marsh in May and June as they normally do and we expected them to establish territories. Surprisingly, it appears that none did. A territory is defined as being established when a singing male is found at the same location after a week. None of the males were found near the same spot on additional surveys as when they were initially identified, and none appeared to be present anywhere at Dyke Marsh after mid-June. And the northern parula? The first one wasn’t even identified until Independence Day, and this bird was probably a post-breeder arriving from outside Dyke Marsh.

So, what is happening to these songbirds? Some species such as the Baltimore Oriole seem to be pushing its range north, so perhaps fewer are staying to breed in the mid-Atlantic. For other songbird species, a possible explanation is the death of all the Pumpkin Ash at Dyke Marsh. As the ash died along the periphery of the marsh, the defoliated trees left nests more exposed to predators like crows and brood parasites like Brown-headed Cowbirds. This explanation does not provide a reason why some species continue to prosper while others appear more vulnerable, but it merits consideration. Additional surveys may provide answers.

Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) collectively built seven nests in 2018. Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) disrupted osprey nesting attempts on Dyke and Coconut Islands in 2017 and ospreys did not try to build nests on either island in 2018. There also was no nesting attempt on Bird Island because the nest tree toppled over during the previous winter. Dyke Marsh did gain a new nest in 2018, but it was a rather pathetic affair. An apparently inexperienced osprey attempted to construct a nest in a tree in the parking lot of the marina, but nesting material fell faster from the nest than the bird could replace it. The bird finally gave up and resumed construction in the woods adjacent to the south picnic area. This nest held firm when completed, but by that time it may have been too late in the year to produce young. This nest and another along the shoreline of the river east of the Big Gut were the only osprey nest failures of 2018. The remaining five nests, including the now extremely popular one on the platform near the boat launch at the marina, fledged from one to three young.

|

|

|

Adult bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) |

|

Bald eagles were highly successful during the 2018 breeding season. The Haul Road bald eagle pair, in its first breeding season, produced a single nestling that successfully fledged by June 10. Further south, the bald eagle pair occupying the nest just south of Tulane Drive fledged three young and the Morningside Lane nesting pair fledged at least one young. Bald eagles have been nesting for a decade at Dyke Marsh and there is now no doubt that the species is an established breeder.

The Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey has a host of wonderful citizen-scientist volunteers whose efforts make the survey possible. The Friends of Dyke Marsh and I as the compiler are grateful to all who volunteer time and expertise to gather essential data. Those who contributed to the 2018 Breeding Bird Survey are listed below.

In alphabetical order, they are as follows: Mercedes Alpizar, Andy Bernick, Eldon Boes, Ashley Bradford, Ed Eder, Jane Gamble, Lori Keeler, Elizabeth Ketz-Robinson, Todd Kiraly, Larry Meade, Roger Miller, Gary Myers, Nick Nichols, Marc Ribaudo, Don Robinson, Laura Sebastianelli, Kimberly Sharp, Phil Silas, Robert Smith, Dixie Sommers, Carol Stalun, Sherman Suter, John Symington, Margaret Wohler, Katherine Wychulis, William Young.

Confirmed - 38 Species: Canada Goose, Wood Duck, Mallard, Mourning Dove, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Northern Flicker, Eastern Phoebe, Great Crested Flycatcher, Eastern Kingbird, Warbling Vireo, Blue Jay, Fish Crow, Purple Martin, Tree Swallow, N. Rough-winged Swal- low, Barn Swallow, Carolina Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, Caroli- na Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, American Robin, Gray Catbird, Northern Mockingbird, European Starling, House Sparrow, House Finch, American Goldfinch, Song Sparrow, Orchard Ori- ole, Baltimore Oriole, Red-winged Blackbird, Common Grackle, Prothonotary Warbler, Yellow Warbler, Northern Cardinal.

The 2018 Breeding Bird Survey Results:

Probable - 6 Species: Least Bittern, Pileated Woodpecker, Marsh Wren, Brown-headed Cowbird, Common Yellowthroat, Indigo Bunting.

Possible - 16 Species: American Black Duck, Wild Turkey, Chimney Swift, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Green Heron, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Cooper’s Hawk, Hairy Woodpecker, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Acadian Flycatcher, White-eyed Vireo, Red-eyed Vireo, White-breasted Nuthatch, House Wren, Cedar Waxwing, Northern Parula.

Present - 5 Species: Caspian Tern, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, Magnolia Warbler.

Definition of Categories:

Confirmed Breeder: Any species for which there is at minimum evidence of a nest. A species need not successfully fledge young to be placed in the confirmed category.

Probable Breeder: Any species engaged in pre-nesting activity, such as a male on territory, courtship behavior, or even the presence of a pair, but for which there is no evidence of a nest. Since birds can and do sing and display to females during migration, this category cannot be used until the safe dates are reached.

Possible Breeder: Any species, male or female, observed in suitable habitat, but giving no hard evidence of breeding. Unless actively breeding, all birds in suitable habitat before the start of the safe date are placed in this category.

Present: Any species observed that is not in suitable habitat or out of its breeding range. It also applies to colonial water birds in the survey tract not associated with a rookery in the tract.

Definition of Safe Dates

We use safe dates as a means of deciding if a bird can be considered a breeder or a migrant. Safe dates are simply defined as a period beginning when all members of a given species have ceased to migrate in the spring and ending when they begin to migrate in the fall. Unless a bird is engaged in behavior that confirms breeding, it will be placed no higher than in the possible breeder category if it is observed outside the safe dates assigned to that species.

The Results of the 2017 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey

By Larry Cartwright, Breeding Bird Survey Coordinator

The 2017 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey was conducted between Saturday, May 27 and Tuesday, July 4, but any data collected outside of this period that confirmed a breeding species was entered into the database. This permitted us to filter out most migrants that do not use the marsh or surrounding habitat to breed. I also included information provided from the Sunday morning walks and reliable individuals to supplement data reported by the survey teams. The survey tract encompasses the Belle Haven picnic area, the marina, the open marsh, that portion of the Big Gut known as West Dyke Marsh that extends from the George Washington Memorial Parkway west to River Towers, the Potomac River from the shoreline to the channel, and the surrounding woodland from the mouth of Hunting Creek to south of Morningside Lane.

Our methodology uses behavioral criteria to determine the breeding status of each species that is recorded in the survey tract. Species are placed into one of four categories: confirmed breeder, probable breeder, possible breeder, and present. We found 87 species at Dyke Marsh during 2017. There were 46 confirmed breeding species, 8 probable breeders, and 11 possible breeders. An additional 14 species were documented as present, but either were not in suitable breeding habitat, were colonial breeding waterbird species not using a rookery inside the survey tract, or out of range.

|

|

| A territorial Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris) in the south marsh. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

Marsh wrens (Cistothorus palustris) were last confirmed as Dyke Marsh breeders in 2014 with approximately 16 singing males and fewer than a dozen nests confined to the marsh vegetation north of Haul Road. Marsh wrens disappeared from the Big Gut in the south marsh after 2006, but a few birds returned to occupy a tributary of the Big Gut that we unofficially call the Northeast Passage between 2011 and 2013. They failed to return to the south marsh in 2014. In 2015 and 2016 no more than three singing males were documented in the marsh surrounding Haul Road. There was no confirmed nesting and Marsh wrens dropped to a probable breeder status.

The same sparse representation of marsh wrens was present around Haul Road during the 2017 survey, but surprisingly two or three males in the south marsh occupied territory in the Northeast Passage after a three-year absence. During a June 25 survey, a canoe team spotted a marsh wren carrying nesting material. A subsequent canoe trip to the Northeast Passage reported three marsh wren nests. Two were apparent dummy nests, built by males to attract females. However, the third nest contained interior lining characteristic of active nests that are accepted and completed by females. A territorial male was close to the nest. Based on this information, I determined that this lone nest was active and met the criteria to confirm breeding.

I caution against interpreting this one active nest as potentially leading to a return of a viable marsh wren breeding population. The decline in the fortunes of this species at Dyke Marsh has been an ongoing process for over two decades. It may be part of a regional decline. Hopefully the marsh restoration will lead to some stability in the marsh habitat and in the absence of other unforeseen negative influences, the marsh wren may establish a presence that we can once again enjoy.

|

|

| A Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) peers from the marsh vegetation on Dyke Island. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

The least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis)is another species at Dyke Marsh that receives our special attention. Our survey teams have documented the retreat of least bitterns from the southern portion of the Big Gut, apparently because of the accelerated erosion. The data collected during the 2017 survey suggests that there is a strong presence of least bitterns at least in some areas of Dyke Marsh. Three separate surveys conducted on June 25, two by canoe and one by foot, collectively reported nine least bitterns. Five of the birds were in the north marsh, including two breeding pairs in a tributary of the Little Gut along the southern edge of the Haul Road peninsula, and the remaining four were in the upper portion of the Big Gut. Additional breeding pairs also were identified near the Northeast Passage and close to the boardwalk at the end of the Haul Road peninsula during other June surveys. Despite these apparent positive signs, we found no least bittern nests or fledged young and least bittern could only be listed as a probable breeder. My primary concern is that least bitterns are being forced into increasingly smaller areas of acceptable breeding habitat at Dyke Marsh and that these heavier concentrations will have a negative impact on breeding success. It seems odd to be able to document least bittern activity in northern locations of the marsh while the entire southern half of the Big Gut remains devoid of these birds.

An interesting relationship developed between ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) and bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) at Dyke Marsh during the 2017 breeding season. Volunteers documented ten active osprey nests in an area extending from Porto Vecchio in the north to Angel Island in Pipeline Bay. Five of these nests, including the highly visible nest at the marina, produced fledged young while the remaining five failed. Two of the osprey nesting attempts were disrupted by a pair of bald eagles. The bald eagles in question could have been the Tulane Drive breedng pair, whose nest also failed by early April or a confused bald eagle duo that started building a nest along Haul Road in June when most eagle nests would be fledging young. A pair of bald eagles was first reported perched beside the osprey nest on Dyke Island on April 7, effectively blocking repeated attempts by the osprey breeding pair to access the nest. The bald eagles soon became interested in the osprey nest on the adjacent Coconut Island and perched beside this nest as well. With the larger and more dominant eagles controlling the situation on the islands, both osprey pairs eventually abandoned their breeding efforts. The bald eagles never made any attempts to destroy or use either the Dyke or Coconut Island nests but seemed content in just preventing the ospreys from using them.

Bald eagles did have a successful breeding record in 2017. The Morningside Lane breeding pair had at least one healthy, active youngster in the nest last seen on June 8. The bird apparently fledged within the following week.

|

|

| A female Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia ) feeds a much larger Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) fledgeling. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

Dyke Marsh hosts a respectable number of neotropical migrant songbirds, including great crested flycatchers (Myiarchus crinitus), eastern kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus), warbling vireos (Vireo gilvus), yellow warblers (Setophaga petechia), orchard orioles (Icterus spurius), and baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula), that are confirmed as breeders every year. A walk down Haul Road will likely reveal all six species to the careful observer. Sometimes the careful observer turns out to be a female brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater). One observer on July 7 reported a bedraggled female yellow warbler feeding two brown-headed cowbird fledglings that were bigger and likely outweighed her.

Most songbirds are careful about concealing nests to protect them from predators and brood parasites like brown-headed cowbirds that victimized the unfortunate yellow warbler. Eastern kingbirds sometime don’t concern themselves with such incidentals as nest concealment. During a June 18 canoe survey into the Big Gut, I was surprised to find a completely exposed eastern kingbird nest with nestlings about 40 feet up in a dead sycamore. Another canoe team doing a different route on the same day also reported an exposed eastern kingbird nest containing nestlings, this one just four feet off the ground. Eastern kingbirds are quite aggressive and perhaps this aggressiveness just might help negate the need for complete caution and total nest concealment.

Several years ago, I noticed a trend for mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) hens to have delayed single broods or perhaps even multiple broods containing fewer young. In the 1990s, the norm would be to observe a mallard hen in April or May with perhaps a half dozen or more recently hatched young in tow. After 2000, volunteers noticed mallard hens with as few as two or three recently hatched ducklings much later in the summer. Volunteers still reported large broods after 2000, but with reduced frequency. The 2017 breeding season now holds the record for reduced size late broods at Dyke Marsh. On September 17, several volunteers observed a mallard hen in the marina in the company of two youngsters no more than one week old. A review of my records indicates that this is the first September record for breeding mallards since I became compiler in 1994. I have speculated in an earlier report that perhaps small broods were the result of increased predation of young, but significant loss of ducklings in a brood only a few days old seems highly unlikely. An egg predator would probably consume the whole clutch. Therefore, I tend to discount predation as a significant cause of small broods. We often see these small brood young several weeks after hatching and they appear quite healthy, so survival rates may be good in the first months of their lives. The data also shows that breeding bird survey observers often report the cavity nesting wood duck (Aix sponsa) with smaller than normal broods at Dyke Marsh. There may be explanations here that I have not yet entertained. Research continues.

The Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey is impossible without the effort and dedication of participating citizen-scientists that conduct the surveys. This year’s participants included Eldon Boes, Glenda Booth, Marla Brin, Ed Eder, Myriam Eder, Renee Grebe, Susan Haskew, Gerry Hawkins, Elizabeth Ketz-Robinson, Dorothy McManus, Ginny McNair, Larry Meade, Roger Miller, Heidi Moyer, Sasha Munters, Nick Nichols, Rich Rieger, Don Robinson, Laura Sebastianelli, Phil Silas, Robert Smith, Karen Snape, Ned Stone, Sherman Suter, Todd Kiraly, Brett Wohler, Marcus Wohler and Margaret Wohler.

The 2017 Breeding Bird Survey Results:

Confirmed - 46 Species: Canada Goose, Wood Duck, Mallard, Mourning Dove, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Pileated Woodpecker, Eastern Phoebe, Great Crested Flycatcher, Eastern Kingbird, Warbling Vireo, Red-eyed Vireo, Blue Jay, Fish Crow, Purple Martin, Tree Swallow, N. Rough-winged Swallow, Barn Swallow, Carolina Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, Marsh Wren, Carolina Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, American Robin, Gray Catbird, Brown Thrasher, Northern Mockingbird, European Starling, Cedar Waxwing, House Sparrow, House Finch, American Goldfinch, Orchard Oriole, Baltimore Oriole, Red-winged Blackbird, Brown-headed Cowbird, Common Grackle, Prothonotary Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Northern Parula, Yellow Warbler, Northern Cardinal, Indigo Bunting.

Probable - 8 Species: Chimney Swift, Least Bittern, Barred Owl, Hairy Woodpecker, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Acadian Flycatcher, White-breasted Nuthatch, Song Sparrow.

Possible - 22 Species: American Black Duck, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Common Gallinule, Spotted Sandpiper, Green Heron, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Red-shouldered Hawk, Red-tailed Hawk, Eastern Screech Owl, Great Horned Owl, Belted Kingfisher, Northern Flicker, Willow Flycatcher, American Crow, House Wren, Wood Thrush, Eastern Towhee, Louisiana Waterthrush, Kentucky Warbler, American Redstart, Scarlet Tanager, Blue Grosbeak.

Present - 11 Species: Ring-necked Duck, Rock Pigeon, Ring-billed Gull, Caspian Tern, Forster’s Tern, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, Black Vulture, Turkey Vulture, Blackpoll Warbler.

Definition of Categories:

Confirmed Breeder: Any species for which there is at minimum evidence of a nest. A species need not successfully fledge young to be placed in the confirmed category.

Probable Breeder: Any species engaged in pre-nesting activity, such as a male on territory, courtship behavior, or even the presence of a pair, but for which there is no evidence of a nest. Since birds can and do sing and display to females during migration, this category cannot be used until the safe dates are reached.

Possible Breeder: Any species, male or female, observed in suitable habitat, but giving no hard evidence of breeding. Unless actively breeding, all birds in suitable habitat before the start of the safe date are placed in this category.

Present: Any species observed that is not in suitable habitat or out of its breeding range. It also applies to colonial water birds in the survey tract not associated with a rookery in the tract.

Definition of Safe Dates

We use safe dates as a means of deciding if a bird can be considered a breeder or a migrant. Safe dates are simply defined as a period beginning when all members of a given species have ceased to migrate in the spring and ending when they begin to migrate in the fall. Unless a bird is engaged in behavior that confirms breeding, it will be placed no higher than in the possible breeder category if it is observed outside the safe dates assigned to that species.

The Results of the 2016 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey

By Larry Cartwright, Breeding Bird Survey Coordinator

The 2016 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey was conducted between Saturday, May 28 and Monday, July 4, but any data collected outside of this period that confirmed a breeding species was entered into the database. This permitted us to filter out most migrants that do not use the marsh or surrounding habitat to breed. I also included information provided from the Sunday morning walks and reliable individuals to supplement data reported by the survey teams. The survey tract encompasses the Belle Haven picnic area, the marina, the open marsh, that portion of the Big Gut known as the West Marsh that extends from the George Washington Memorial Parkway west to River Towers, the Potomac River from the shoreline to the channel, and the surrounding woodland from the mouth of Hunting Creek to south of Morningside Lane.

The Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey is undertaken as part of a continuing biological inventory of the tidal wetlands. Our methodology uses behavioral criteria to determine the breeding status of each species that is recorded in the survey tract. Species are placed into one of four categories: confirmed breeder, probable breeder, possible breeder, and present. Volunteer teams in 2016 collectively reported 86 species at Dyke Marsh between May 28 and July 4. The 2016 list contains 44 confirmed breeding species, 12 probable breeders, and 16 possible breeders. The remaining 14 species were present, but either were not in suitable breeding habitat, were colonial breeding waterbird species not using a rookery inside the survey tract, or out of range.

Marsh Wrens failed to breed at Dyke Marsh for the second consecutive year. Possibly three males briefly established territories north of the Haul Road peninsula, that portion of the path from the dogleg to the boardwalk, but they appeared to abandon the effort by the middle of June. Least Bitterns had better success. As in 2015, Least Bitterns concentrated breeding efforts in the marsh vegetation surrounding Haul Road, in the tributaries of the Little Gut, and the upper portion of the Big Gut. However, only one or two birds were reported by each survey team in 2016 compared to 2015 when survey teams submitted weekly reports of three to five birds.

|

|

|

Least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) perched in ash tree near the boardwalk in Dyke Marsh. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

I am unable to determine whether the reduction in Least Bittern numbers reflects an actual decline of Least Bitterns between 2015 and 2016 or if other factors were involved. Future surveys will give a clearer picture. We do know that a minimum of one Least Bittern breeding pair successfully raised young in 2016. A pair that was reported along the Haul Road boardwalk in early June was joined by a fledged youngster on July 9.

The retraction of the Least Bittern from the lower portion of the Big Gut can be attributed to the heavy erosion occurring there. The complete disappearance of the Marsh Wren as a breeder around the Haul Road in 2015 may be part of a regional decline while erosion perhaps played a contributing factor in the elimination of the species as a breeder in the Big Gut almost a decade ago. Reliable reporters who frequent regional wetlands in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have noted the decline and disappearance of Marsh Wrens in areas the birds used to inhabit.

The usual contingent of migratory songbirds arrived at Dyke Marsh beginning in April and

|

|

| A male orchard oriole (Icterus spurius) in a sycamore tree brought a mayfly, a spider and worms to the nestlings. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

had what seemed to be a particularly successful year. There was a surprisingly high concentration of breeding activity between the Haul Road dogleg and the boardwalk. Volunteers documented five Orchard Oriole nests, two Baltimore Oriole nests, three Yellow Warbler nests, three Eastern Kingbird nests, one Warbling Vireo nest, and several Blue-gray Gnatcatcher nests along this stretch of the Haul Road. One Sycamore beside the wooden bridge hosted four nests!

Survey team reports indicated that over half these nests, including all three Yellow Warbler nests, produced young. One Baltimore Oriole breeding pair nesting in a Sycamore near the short overlook path to the Little Gut was particularly lucky. On May 21 an observer noted crows attempting to ransack the nest while the orioles made a seemingly unsuccessful effort to protect it. I jotted down in my notes that the nest had failed, but the orioles returned within a day. Apparently the damage inflicted on the nest was minimal or at least repairable because the nest owners went on to produce healthy fledglings from this effort. Blue-gray Gnatcatchers were exceptionally lucky in producing young on the Haul Road peninsula except for one breeding pair that was tending to a Brown-headed Cowbird. This one documented case of brood parasitism seemed to be the exception as healthy young Blue-gray Gnatcatchers were easy to find as the breeding season progressed.

The significant Pumpkin Ash die off may be having at least a temporarily beneficial impact on some cavity nesting species such as woodpeckers. For example, a team conducting a canoe survey in the south marsh in early June reported two pairs of Hairy Woodpeckers. Volunteers doing the same route three weeks later tallied five Hairy Woodpeckers, including an adult in the company of a fledged youngster. A Sunday morning Dyke Marsh walk leader in the north marsh also noted an adult Hairy Woodpecker with a young bird. These reports show a larger presence of Hairy Woodpeckers than observed in most previous years. Perhaps the number of dead trees in the wooded area has expanded feeding and breeding opportunities for the Hairy Woodpecker and similar species that use cavities.

I found the presence of Eastern Bluebirds at two locations in the south marsh during 2016 quite interesting and wonder if it is also possibly related to the increased availability of nest cavities. Eastern Bluebirds have not been recorded as breeders in the 23 years that I have compiled the Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey. Yet a bird found at the Big Gut Bridge just north of Tulane Drive during Memorial Day weekend was still singing at this location on June 27, exactly a month later. The habitat at the Big Gut Bridge consists of trees with many snags for nesting, but limited feeding habitat for a ground foraging species like Eastern Bluebird, except for the strip of short grass lining the George Washington Memorial Parkway. However, a report of a bluebird investigating a potential nest cavity at the southernmost point of Dyke Marsh suggests that this species might eventually be added to the list of Dyke Marsh breeding avifauna.

My speculation about the expansion of nesting opportunities for some species that breed in cavities possibly contradicts a statement I made in my 2015 report concerning a likely decline in available cavities for Prothonotary Warblers, another Dyke Marsh breeder. Perhaps there really is no contradiction. Prothonotary Warblers have more selective nesting requirements than other cavity nesters. We generally find Prothonotary Warbler nest cavities at Dyke Marsh no higher than eye level in a snag near or over open water. Many of these snags are located along the banks of the south marsh and Big Gut, and seem to be falling over with increasing rapidity as erosion accelerates.

It should not be surprising considering their habitat requirements that past surveys show Prothonotary Warbler males occupying territories almost exclusively in the south marsh and Big Gut. In 2015, I estimate that up to nine Prothonotary Warblers established territories from the Big Gut Bridge to the southern tip of Dyke Marsh just below Morningside Lane. No males were recorded in the north half of Dyke Marsh during the height of the 2015 breeding season.

A different situation emerged in 2016. Volunteers documented at the beginning of the survey up to three singing Prothonotary Warbler males along the Haul Road and adjacent Coconut (previously referred to as Cormorant) Island just east of the boardwalk. It soon became clear that the birds were there not as a fluke, but had established territory. There also appeared to be a corresponding decline of territorial males in the southern half of the marsh. I have no ready explanation for this phenomenon, except to note that the wooded area around the Haul Road seemed to be wetter than in previous years and perhaps this provided the conditions suitable for breeding. Whatever the case, on June 22, a male that multiple surveyors reported at or near the entrance of Haul Road since early June, was documented carrying food toward the marina, presumably to hungry nestlings.

Ospreys constructed nine nests in the survey tract during 2016 and volunteers documented seven of these containing young. The fate of the female Osprey occupying the platform nest at Porto Vecchio illustrates the dangers all that breeding birds potentially face. It seems that during nest building, the birds brought sticks to the nest that contained fishing line filament. Unfortunately, the female reportedly became entangled in the filament on April 18 and died before she could be rescued. However, the remaining filament was removed, and the male amazingly secured another female to incubate the four eggs now in the nest. And yes, this was one of the seven successful Osprey nests that produced healthy youngsters. The popular marina nest produced two nestlings, one of which died soon after hatching, while the other went on to fledge before Independence Day.

|

|

| The Tulane Drive bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) nest produced two fledged young. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

Finally, The Tulane Drive Bald Eagle nest produced two fledged young in 2016. Although all three resident owl species were present during the 2016 survey, the best we could find was a pair of Barred Owls. There were no fledged owl young this year.

The Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey would not be possible except for the effort and dedication of the participating citizen-scientists that conduct the surveys. The Friends of Dyke Marsh are grateful to all who volunteer time and expertise to gather accurate data that make this survey a success. We extend a deep appreciation and thank you to all participants. Those who contributed to the 2016 Breeding Bird is some capacity are listed below:

In alphabetical order, they are: David Arnold, Eldon Boes, Glenda Booth, Ed Eder, Myriam Eder, Sandy Farkas, Kurt Gaskill, Susan Haskew, Gerry Hawkins, Lori Keeler, Elizabeth Ketz-Robinson, Claire Kluskens, Ginny McNair, Larry Meade, Roger Miller, Nick Nichols, Marc Ribaudo, Rich Rieger, Don Robinson, Laura Sebastianelli, Phil Silas, Ned Stone, Jessie Strother, Sherman Suter, Marcus Wohler, Margaret Wohler, Katherine Wychulis.

The 2016 Breeding Bird Survey Results:

Confirmed - 44 Species: Canada Goose, Wood Duck, Mallard, Least Bittern, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Mourning Dove, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Northern Flicker, Acadian Flycatcher, Eastern Phoebe, Great Crested Flycatcher, Eastern Kingbird, Warbling Vireo, Blue Jay, American Crow, Fish Crow, Purple Martin, Tree Swallow, N. Rough-winged Swallow, Barn Swallow, Carolina Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, White-breasted Nuthatch, Carolina Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, American Robin, Gray Catbird, Brown Thrasher, Northern Mockingbird, European Starling, House Sparrow, House Finch, Prothonotary Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, Northern Cardinal, Red-winged Blackbird, Common Grackle, Brown-headed Cowbird, Orchard Oriole, Baltimore Oriole.

Probable - 12 Species: Barred Owl, Pileated Woodpecker, Eastern Wood-Pewee, White-eyed Vireo, Red-eyed Vireo, Marsh Wren, Eastern Bluebird, Cedar Waxwing, American Goldfinch, Norhtern Parula, Song Sparrow, Indigo Bunting.

Possible - 16 Species: Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Chimney Swift, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Killdeer, Spotted Sandpiper, Green Heron, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Cooper’s Hawk, Redshouldered Hawk, Red-tailed Hawk, Eastern Screech Owl, Great Horned Owl, Belted Kingfisher, Willow Flycatcher, House Wren, Yellow-throated Warbler.

Present - 14 Species: Tundra Swan, Lesser Scaup, Rock Pigeon, Whimbrel, Laughing Gull, Ring-billed Gull, Herring Gull, Caspian Tern, Double-crested Cormorant, Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, Black Vulture, Turkey Vulture, Bank Swallow.

Definition of Categories:

Confirmed Breeder: Any species for which there is at minimum evidence of a nest. A species need not successfully fledge young to be placed in the confirmed category.

Probable Breeder: Any species engaged in pre-nesting activity, such as a male on territory, courtship behavior, or even the presence of a pair, but for which there is no evidence of a nest. Since birds can and do sing and display to females during migration, this category cannot be used until the safe dates are reached.

Possible Breeder: Any species, male or female, observed in suitable habitat, but giving no hard evidence of breeding. Unless actively breeding, all birds in suitable habitat before the start of the safe date are placed in this category.

Present: Any species observed that is not in suitable habitat or out of its breeding range. It also applies to colonial water birds in the survey tract not associated with a rookery in the tract.

Definition of Safe Dates

We use safe dates as a means of deciding if a bird can be considered a breeder or a migrant. Safe dates are simply defined as a period beginning when all members of a given species have ceased to migrate in the spring and ending when they begin to migrate in the fall. Unless a bird is engaged in behavior that confirms breeding, it will be placed no higher than in the possible breeder category if it is observed outside the safe dates assigned to that species.

The Results of the 2015 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey

By Larry Cartwright, Breeding Bird Survey Coordinator

The 2015 Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey was con-ducted between Saturday, May 23 and Sunday, July 5, but any data collected outside of this period that confirmed a breeding species was entered into the database. This permitted us to weed out most migrants that do not use the marsh to breed. I also included information provided from the Sunday morning walks and reliable individuals. In previous years, the survey tract encompassed the Belle Haven picnic area, the marina, the open marsh, the Potomac River from the shoreline to the channel, and the surrounding woodland from the mouth of Hunting Creek to south of Morningside Lane. In 2015 we added the West Marsh to the survey tract. The West Marsh is defined as that portion of the Big Gut and the surrounding woodland that lies west of the George Washington Memorial Parkway up to River Towers.

The Dyke Marsh Breeding Bird Survey is undertaken as part of a continuing biological inventory of the tidal wetlands. The breeding status of each species is determined by means of behavioral criteria. Species are placed into one of four categories: confirmed breeder, probable breeder, possible breeder, and present. Volunteer observers participating in the 2015 survey reported 84 species at Dyke Marsh between May 23 and July 5. The 2015 list contains 48 confirmed breeding species, four probable breeders, and 13 possible breeders. An additional 19 species were present, but either were not in suitable breeding habitat, were colonial breeding waterbird species not using a rookery inside the survey tract, or out of range.

|

|

| Marsh wrens (Cistothorus palustris) dropped from confirmed breeder status in this year's survey. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

There was a void in the marsh during the 2015 breeding season, a profound absence in the Narrowleaf Cattails that have supported the nests of Marsh Wrens for so many years. The Dyke Marsh breeding population of Marsh Wrens failed to arrive in 2015. Canoe teams reported two calling Marsh Wrens on the large island north of the Haul Road peninsula for the first time only in early July, but at that late date, I believe that these birds were possibly relocated failed breeders from another population. Whatever the case, Marsh Wrens dropped from their normal status as Dyke Marsh confirmed breeders to merely possible breeders in 2015.

The failure of Marsh Wrens in 2015 to arrive and occupy the marsh during spring migration in May was hardly unexpected. In her study of Marsh Wrens at Dyke Marsh in 1998 and 1999 as part of her Master’s Thesis, Population Abundance and Habitat Requirements of the Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris) at Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve: An Urban Conservation Challenge, Sandy Spencer found slightly less than three dozen territorial males at Dyke Marsh. Sandy pointed out that Marsh Wrens were once abundant along the Potomac River close to Washington DC, but were experiencing declines by the 1960s. Habitat loss was the overriding cause, but Sandy also saw additional problems with the Dyke Marsh breeding population, including high rates of nest predation, and narrow preferences for nesting territories. She speculated that this could put the Marsh Wren breeding population at risk over the long term.

Sandy’s concern was warranted. Soon after her study, the number of territorial or singing males dropped from less than three dozen to around 18. The decline was more immediately noticed in the Big Gut portion of the south marsh. The birds disappeared from the Big Gut for several years and then briefly returned between 2011 and 2013, with an active nest documented in 2013. Then in 2014, there were no Marsh Wrens to be found anywhere in the Big Gut.

The Marsh Wren population in the north marsh was centered around the Narrowleaf Cattails to the north of the Haul Road peninsula and the largest of the adjacent islands. After 2000, the number of singing male Marsh Wrens in the north marsh fluctuated from an estimated low of eight to a high of perhaps 16. In 2015, we had absolutely nothing except the late arriving males. The unfortunate loss of Marsh Wrens at Dyke Marsh may be a result of an overall regional decline exacerbated by conditions unique to Dyke Marsh, based on Sandy’s thesis and conversations with local experts and experienced birders (see article p. 2). We hope that the absence of Marsh Wrens will be temporary as we prepare for marsh restoration, but know that there are no guarantees.

|

|

| A recently fledged least bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) improving its fishing skills. Photo by Ed Eder |

|

In contrast to the sad tale of Marsh Wrens, Least Bitterns appeared to have a decent breeding season. During the 2015 survey, Least Bitterns were concentrated in the tributaries of the Little Gut and the channel that separates the Haul Road peninsula from the largest island to the north. Volunteers reported smaller numbers of Least Bitterns at the end of the peninsula just east of the boardwalk, on the north side of the large island, and in the inlet adjacent to the north side of the dogleg. Numbers appeared to be slightly reduced in the Big Gut, but the birds were not impossible to find. It may be that Least Bitterns are gradually withdrawing from the southern half of the Big Gut, possibly as erosion accelerates, and concentrating in the northern half. That, however, is still speculation on my part and bears a close look during the 2016 survey.

Least Bittern youngsters were found, not surprisingly, in areas of their heaviest concentration during the 2015 survey. In late July, I received reports of a fledged Least Bittern and then a family group in the channel separating the Haul Road peninsula from the adjacent island followed a few days later by additional reports of a Least Bittern fledgling attempting to fish in the Little Gut. Admittedly, we conducted more Least Bittern dedicated surveys after Independence Day then we have in the past, but the effort produced positive results. Even during the regular survey, we found more breeding pairs in the marsh, including a pair copulating in one of the Little Gut tributaries, than I can remember in previous years.

I want to add that this does not mean that the Least Bittern will not meet the same fate as the Marsh Wren. One explanation might be that the birds are becoming more concentrated in remaining suitable habitat around the Haul Road peninsula as the marsh erodes in the south, and thus temporarily easier to find at these locations. However, crowded conditions may not be conducive to long term overall breeding success, and provides another reason to keep an eye on these birds in 2016.

Most of our Dyke Marsh raptors had a successful breeding year in 2015. The Morningside Bald Eagle nest was abandoned by January, 2015, but the new nest south of Tulane Drive fledged one healthy youngster by the first week in June. Ospreys constructed a total of 11 nests in the survey tract. Two of these nests were abandoned, but the breeding pair in both cases constructed new nests at different locations. Of the nine active nests, eight fledged youngsters. The highly visible and popular breeding pair at the marina nest saw its three nestlings take their first, but truncated flights, on July 1. One of the breeding pair that abandoned its original nest and rebuilt a second one also fledged youngsters, but at the end of July. Better late than never it seems!

|

|

| Here a barred owl (Strix varia) looks down at its human observers. Photo by Jennifer Cowser |

|

As far as nocturnal raptors are concerned, we hoped to confirm our Eastern Screech-Owl pair as Dyke Marsh breeders. Volunteers documented the pair together, and witnessed copulation, but we could not confirm breeding. That has been the case for several years now. We were in for quite a surprise, however. On April 12, several of us spotted a pair of Barred Owls in a tree in the wooded spot between Marina Road and the south picnic area. One of the birds was raising and lowering its head as if feeding nestlings, but we could not be sure. At least one of the owls was spotted twice after that and then on May 5, I saw the Barred Owl breeding pair near the Haul Road entrance accompanied by a fledged youngster. The Barred Owl family group was perched less than 30 feet from the traditional primary roost cavity of the Eastern Screech-Owls. That’s potentially bad news for an Eastern Screech-Owl because a Barred Owl can easily make a meal out of a smaller owl.

As far as our Dyke Marsh songbirds fared, Eastern Kingbirds, Warbling Vireos, and Orchard Orioles were present in expected decent numbers, and all were confirmed as breeders by the documentation of multiple nests or numerous fledged young and family groups for each species. In one instance, a Warbling Vireo pair in the north picnic area had difficulty with Eastern Kingbird neighbors as the vireos unsuccessfully attempted to prevent the kingbirds from demolishing their nest. Although not as numerous as Eastern Kingbirds, Warbling Vireos, and Orchard Orioles, Eastern Wood-Pewees and Red-eyed Vireos also fledged nestlings, although in one case the youngster being fed by a Red-eyed Vireo parent was a Brown-headed Cowird. American Crows bred at Dyke Marsh for the first time since 2003 when West Nile Virus swept through the area. Fish Crows have dominated the breeding scene at Dyke Marsh since then, but it appears that American Crows are working their way back into the picture.

|

|

| A song sparrow (Melospiza melodia) feeds a fledged youngster. Photo by Laura Sebastianelli |

|

Baltimore Orioles and Prothonotary Warblers were tallied in the confirmed breeder category, but neither species seemed as numerous as in previous breeding seasons. In addition, Northern Parulas, not confirmed as 2015 breeders, seemed to be singing from fewer locations than last year. Maybe this is a result of normal yearly fluctuation in population size, but in the case of Prothonotary Warblers, the seemingly lower numbers may be a result of snags falling over at a faster rate, depriving perhaps some birds of an adequate choice of nest cavities. Brown-headed Cowbirds appeared to have a banner breeding year at Dyke Marsh in 2015, with Eastern Phoebe, Red-eyed Vireo, Song Sparrow, and Northern Cardinal all recorded as host parent species.